One family’s quest for the Delta’s best

Written by Jennifer Stewart Kornegay | Illustrations by Julia Marshall

“Oh! Tamales! Can we get some?” The drive from Montgomery, Alabama, through sheets of rain to reach Greenwood in the Mississippi Delta had worn me out, and I slipped into a weary trance while my Mom perused the menu at the Crystal Grill. Her squealed question snapped me out of it.

It was 2009, and I didn’t know much about hot tamales other than they were a “Delta delicacy,” and since we were in the Delta (and Mom was so excited), we ordered a half dozen. While we waited, she shared a story I’d never heard. During childhood visits with her beloved grandmother in Meridian, Mississippi (not in the Delta), she’d devour batches of tamales scratch-made by a neighbor lady with Delta roots. Minutes later, our waitress delivered a plate of slim packages, their wet cornhusk wrappings tied with twine. Mom undid the string to reveal a cigar-shape of soft, yellow-ish dough. She beat me to the first bite, and I watched her travel back in time. She said they tasted just like she remembered, as she blinked back the moisture threatening to run her mascara.

We quickly polished off the cornmeal shells cradling spicy meat filling. The tamales were the highlight of the meal, but not the evening. I’m a relentless miner of family memories, and learning something new about my mother’s life was like striking gold.

Eight years after my introductory tamale taste, Mom and I set out for the Mississippi Delta again (and this time, brought Dad along too), in search of tamales and their tales. We found a mix of tradition, ingenuity, and a good measure of pride and nostalgia all rolled into this humble food.

Greenville

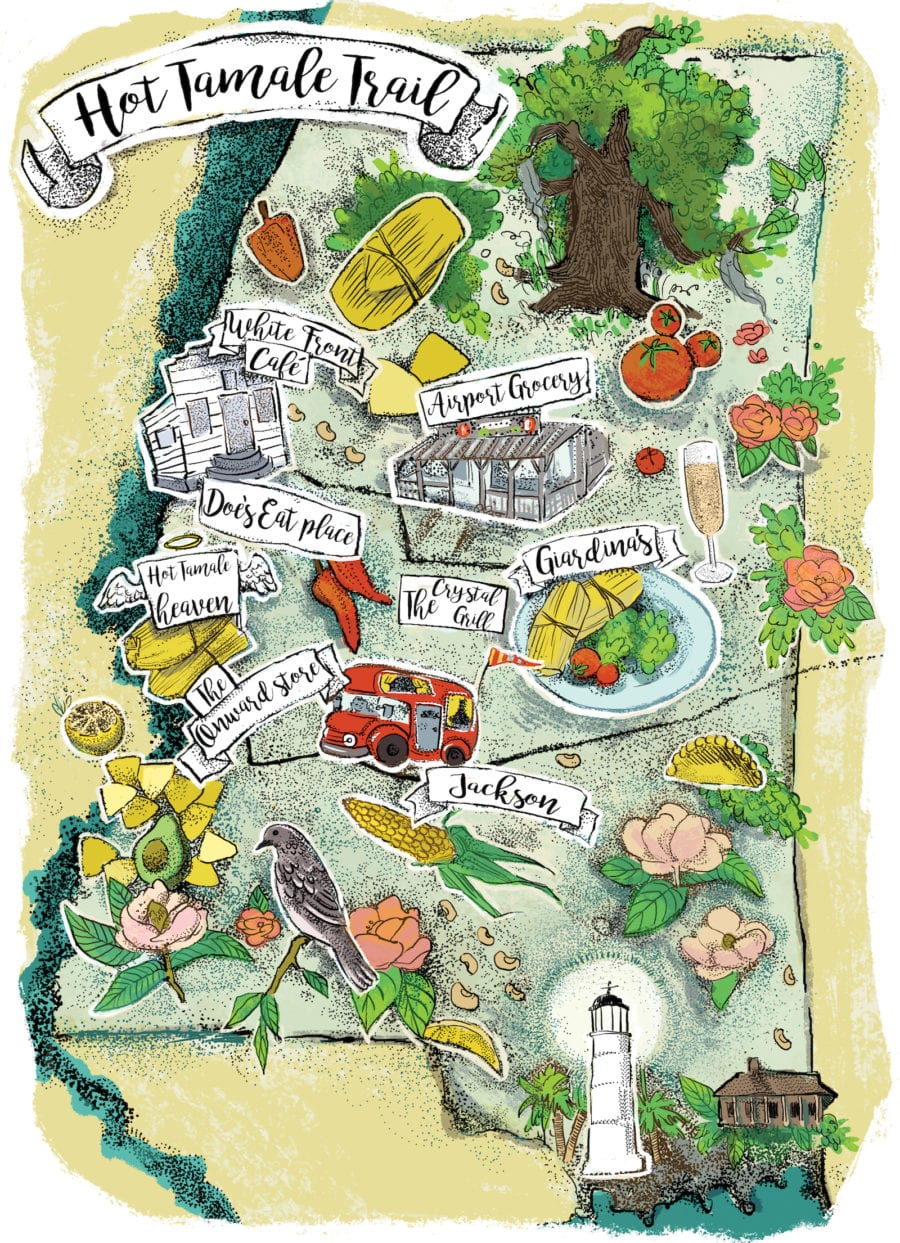

On an early morning in late March, we leave family in Jackson, Mississippi, to head west toward Vicksburg and then up Highway 61 north, following the flow of the Mississippi River. A few miles in, the land whizzing past my window flattens like someone had rolled out the gentle hills. I can’t see the river but know it’s snaking beside us, a currently invisible yet formidable force whose muddy waters created the fertile soil that defines the Delta, a section of the Magnolia State that sprouted the blues—the root of most modern music—alongside cotton stalks.

While Dad keeps double-checking my directions, Mom keeps reminding me to gather an “essential” piece of information. “You’ve got to ask everyone if they put sweet pickle juice on their tamales,” she says. “I want to know if that’s standard or just something my grandmother did.”

Our first stop is the Onward Store, a 100-plus-year-old outpost whose main claim to fame is that it sits near the spot of President Theodore Roosevelt’s famous “teddy bear” hunt in 1902. The general store now houses a gift shop (offering local jams, fresh pork skins, teddy bears, and more), and a cafe. We’re too early for the eatery’s tamales but grab hot coffee before pressing “onward” to Greenville.

Perched on a high point beside the Mississippi River, Greenville has long been a locale flooded with creativity; the small city has produced blues legends and literary luminaries. Contributions to culinary culture earned it the title of “Tamale Capital of the World,” a designation celebrated with its annual Hot Tamale Festival each October.

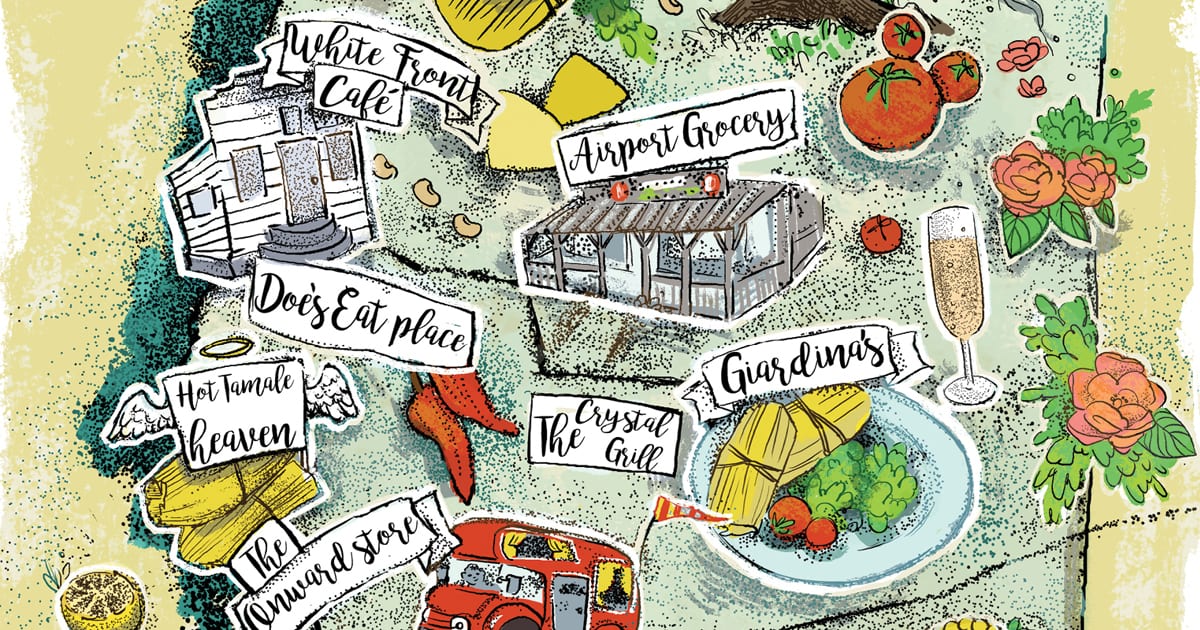

At 9:30 am, we pull up at Doe’s Eat Place. The small building is showing its age, but owner Charles Signa is not. Doe’s is only open for dinner, but he welcomes us with enthusiastic handshakes and bounces through the story behind his restaurant. “It all started with tamales. I think back then, we were one of the only places doing them here,” he says. Signa’s grandfather opened the grocery store turned restaurant in 1903 after emigrating from Sicily. In the late 1930s, Signa’s dad, “Doe,” got a tamale recipe from a friend. “He brought it to my mom, and she tinkered with it, improved it, adding additional spices,” he says. The couple started selling their tamales out of the family store, and by 1941, the spot had fully evolved into a restaurant.

Delta tamales are smaller than their Latin American cousins, with outsides made with cornmeal instead of finer-ground masa.

Doe’s tamales have evolved too. “I think the guy my dad got that first recipe from maybe got it from a Mexican migrant worker,” he says. “We had a lot of them here then, helping on farms. They ate tamales in the fields.” The tamales’ portability made them appealing to African-Americans also working the fields, and their savory scent wafting through rows of cotton was tempting too. They tried them, and started making their own. Soon, their version jumped racial and socio-economic lines to spread across the region. That’s the most prevalent theory, but no matter their exact origins, tamales are now a staple of the area’s food heritage. And they are distinct. Delta tamales are smaller than their Latin American cousins, with outsides made with cornmeal instead of finer-ground masa. And instead of being steamed, they’re boiled in seasoned water.

While serving bits of Doe’s history, Charles puts a white plate down on the table, splashes of orange liquid splattered on its edges, with six parchment-paper-encircled cylinders clustered in its center. Infused with the rich broth they simmered in for hours, each forkful of tamale melts in our mouths.

Up until about twenty-five years ago, Doe’s tamales were encased in cornhusks. But after a husk shortage pushed them to use parchment paper, they never went back. Now, Doe’s is known as much for steaks—hand-cut in-house and served with a side of fries crisped to golden in cast-iron skillets—as it is tamales, but it still sells hundreds a week. Customers get them as an appetizer, and some get a bowl of Doe’s slightly sweet chili for dipping. Some cut them up and eat them on saltines. “I put ketchup on mine,” Charles says. Mom slips her question in: “How about sweet pickle juice? Ever do that or hear of it?” “No, but I’ll try it,” Charles says.

He says we can eat them any way we like, just don’t fill up. “You gotta save room for steak,” Charles says. Heeding that advice may be one reason tamale demand has gone down at Doe’s. Another is more competition. “There are now fifteen or so places doing them here,” Charles says. “But that’s okay. We helped make them popular; they’re part of our story.”

One of those other places in Greenville is Hot Tamale Heaven, where we meet the father-son team Willie and Aaron Harmon. I order a tamale snack to follow my tamale breakfast (Mom and Dad broke Charles’ rule; they’re full), and Willie flashes a broad smile as he plays with his business’ name. “They’re divine,” he says, “and we definitely have faith in our product.” His grin widens as he watches me eat. “Good, right?” Mouth full and mindful of my manners, I nod. Aaron chimes in. “They’re kinda mild, heat-wise, but our flavor is through the roof,” he says. I finish a few traditional tamales before trying the fried version, its crunchy crust a perfect foil for the tender insides.

They don’t taste mass produced, but the company now uses machines that can make 2,500 dozen tamales a day (though they’re still all hand-rolled and hand-tied in cornhusks) to serve at its two locations in Greenville and to sell wholesale to restaurants across the Delta. It all started forty years ago when an elderly lady shared her tamale wisdom with Willie. She didn’t divulge a recipe, just the basic technique, sending him home to come up with his own seasonings. When he felt he had it right, he sold them to neighbors. “It took all day, but I cleared seven dollars,” Willie says. “You’d have thought I made a million.” That success sent him peddling tamales out of his truck until his wife proposed he get her a cart to sell outside of Stein Mart. “She sold thirty dozen the first day,” Willie says. He quit his day job, and Hot Tamale Heaven was ordained. Now it’s an empire that’s still expanding, thanks to Aaron. “I’m so proud to see where he’s taking things,” Willie says.

Cleveland

We leave Greenville heading north and east, bound for Cleveland, passing another expanse of pancake-flat fields dotted with rows of metal silos. Home to Delta State University, Cleveland’s downtown boasts the hip eateries, coffee bars, and boutiques of a college town, making for a nice hour or so of exploring. But a key component of the Delta’s legacy is the blues, so visits to the city’s Grammy Museum Mississippi, nearby Dockery Farms, and other area stops on the Mississippi Blues Trail are worth equal time.

After our tour of the town, Mom and Dad are hungry again (and I always am), so we grab a table at Airport Grocery as its lunch crowd leaves. Like Doe’s, it’s an old grocery store turned restaurant. At night, it will fill up again with folks hungry for its burgers and chicken salad, but also the soul-stirring sounds that pour out of the blues bands playing on its small stage. When the waitress brings our teas and chili-cheese tamales, Mom asks her about the pickle juice. “Never heard of it, but I can go look for some?” she offers. Mom thanks her but declines, and we dig into the tamales, smothered with chili and melted cheddar, knowing they need no further embellishment. Like the fried tamales, they’re good, but we all decide we’re purists and prefer ours plain.

Rosedale

We pile back in the car and head north and west twenty-four miles to Rosedale and the White Front Café. Our large food intake means a nap is necessary for Dad, but Mom and I approach the tiny whitewashed house and read the Mississippi Blues Trail marker out front that outlines how tamales link to the blues. Owner Barbara Pope greets us at the creaky screen door. Soft-spoken but friendly, she lets me question her while she tends to pots, packed with tamales and roiling water, rattling atop a small stove. “I took over from my brother Joe when he passed in 2004, and he had it open about forty years before that,” she says. She has no profound insight on why tamales remain popular, just truth. “They taste good,” she says. “Especially these,” as she hands me a plate of hers, still steaming. I cut a big bite. “These are spicy!” I tell her. My tongue demands a cold drink to go, and upon leaving, we nod our heads in agreement as she insists, “You come back when you’re near.”

Greenwood

On the eastern edge of the Delta, Greenwood is the last city on our list, and on the way there, we rate the tamales we’ve had so far. The differences are subtle. More or less heat. Varying textures and filling-to-shell ratios. A common denominator is the conviction of every maker that their family’s secret blend of spices or specific technique renders the best tamales. By the time we pull into town, none of us can name a clear favorite.

Once the “Cotton Capital of the World,” like other Delta towns the city suffered as agriculture changed. But as we drive downtown, the impact of the Viking Range Company is evident. Founded by Greenwood native Fred Carl in the late 1980s, Viking resurrected much of the city center and brought needed jobs to the entire area.

While the manufacturer of high-end ranges and other kitchen appliances has since been sold, its plant is still in Greenwood, and its headquarters remain downtown, as does the Viking Cooking School and the luxurious Alluvian hotel (where we later slip into a tamale-induced coma), both also owned by Viking. There’s no question Mom and I will begin our elegant dinner at Giardina’s, the hotel’s restaurant, with more tamales; our hankering has not yet been satisfied. As we wonder aloud whether we should have splurged for two orders, my dad blurts out that he doesn’t want any more. “What?” Mom and I ask in unison. “I actually don’t like them,” he says. Maybe the private setting—our table is alone in one of the restaurant’s small curtained booths—spurred him to reveal his secret, but he confesses just as the cuisine in question arrives. They’re already shucked, soaking in rust-colored cooking liquid. We’re all quiet, pondering the tamales he’s eaten with fake gusto and a now-suspiciously timed nap before Mom shrugs and says, “More for us!” and plops one on her plate. They, too, are similar to the others, yet unique. Fluffy with a smoked-peppery bite, they’re the family recipe of the restaurant’s dedicated tamale maker.

The next day, before driving back to Alabama, we have lunch where this all began, at the Crystal Grill. Along with my chef salad and tamales, I get more new information. The restaurant has been open since 1926, but tamales were only added to the menu recently. Current owner Johnny Ballas, whose dad took over from his wife’s brother in the 1950s, explains why he decided to start serving tamales, which he buys from Hot Tamale Heaven. “They are such a big part of the Delta, not having them didn’t seem right,” he says. “They mean something to people here.”

I’m no Delta native, but they now mean something to me too. As we stand up to go, Mom hits Ballas with her pickle-juice query. He’s never heard of it either, making us feel sure it was just her grandmother’s idiosyncrasy. But maybe it won’t always be. If one of the folks Mom asked tries it and likes it, maybe it will catch on. Like cayenne-laced water seeps through husks into meal and meat, one family’s memory just might infuse others.

A TOUR THROUGH THE DELTA TAMALE TRAIL

The Onward Store

6693 Hwy. 61

Rolling Fork, Mississippi

662-873-6809

Doe’s Eat Place

502 Nelson St.

Greenville, Mississippi

662-334-3315

Hot Tamale Heaven

1640 Hwy. 82 E

Greenville, Mississippi

662-378-2240

Airport Grocery

3608 Hwy. 61 N

Cleveland, Mississippi

662-843-4817

White Front Café

902 Main St.

Rosedale, Mississippi

662-759-3842

Giardina’s

314 Howard St.

Greenwood, Mississippi

662-455-4227

The Crystal Grill

423 Carrollton Ave.

Greenwood, Mississippi

662-453-6530

share

in this article

-

Exploring Mississippi: A Quintessential Southern Experience

-

Recipes From Our Summer Issue

by TLP Editors -

Elevate Your AWESOME with an Alpharetta Music Getaway

by TLP's Partners -

9 Noteworthy Tennessee Restaurants | Listen

by Margaret Littman -

Outdoor Adventure and Historic Charm Awaits in St. Martin Parish

by TLP's Partners