The African American diaspora launched a wave of cooking traditions and styles throughout the United States that became synonymous with “Southern,” “comfort,” or “down-home” food. As descendants of enslaved people moved throughout and beyond the South, they adapted old family recipes to meet the changing ingredients and socioeconomic conditions. In the mid-twentieth century, the term “soul food” became broadly used to describe the style of food found in Black communities—a style reflected in many food traditions found in the South.

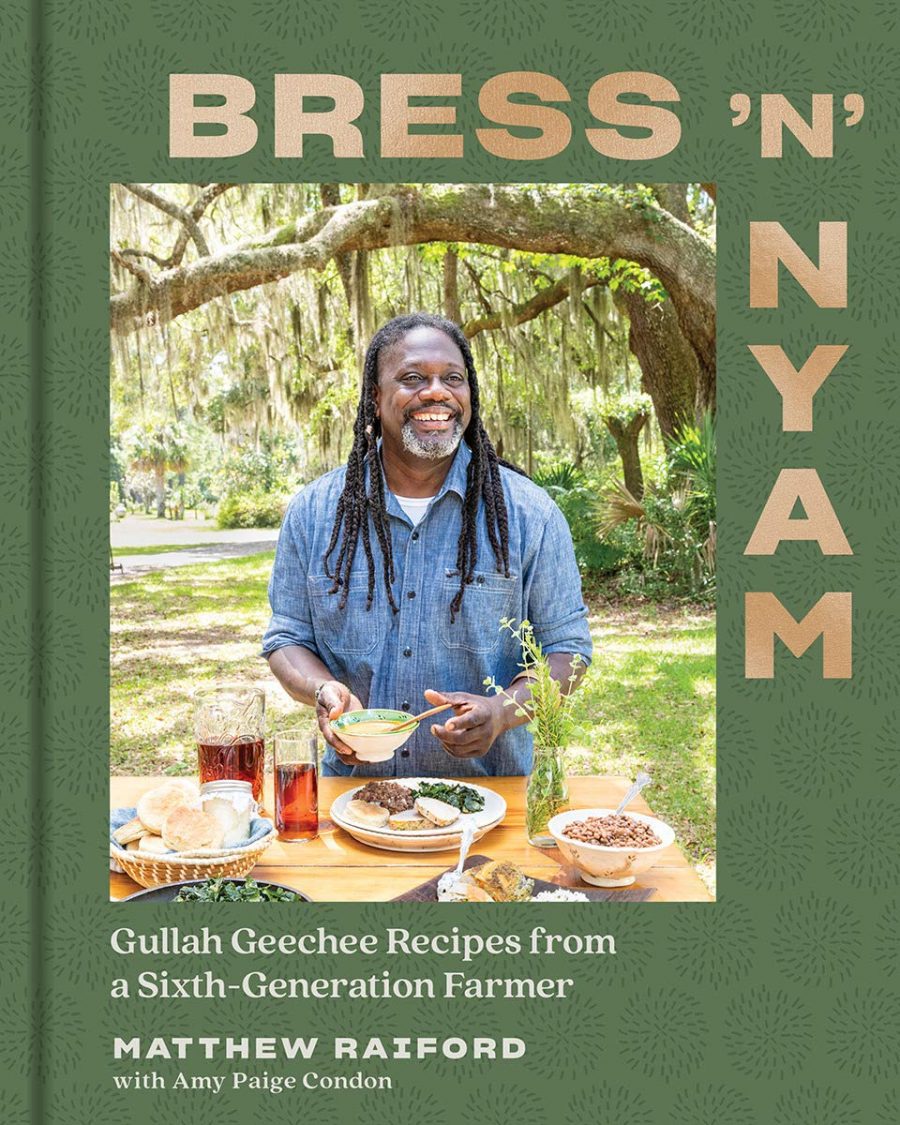

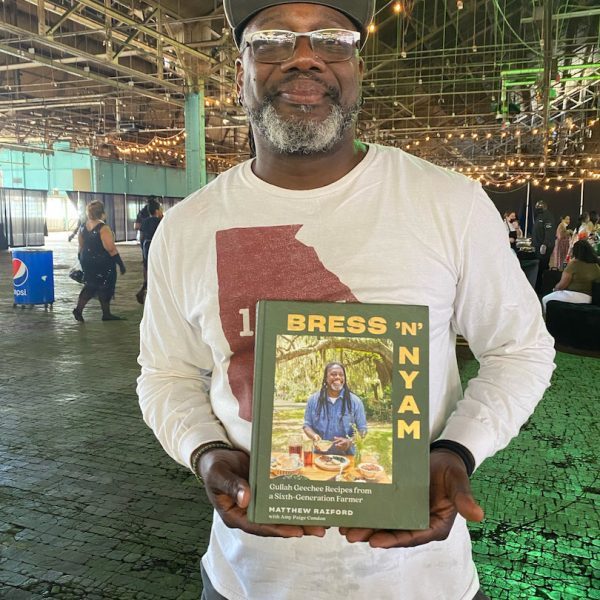

2021’s Gather ‘Round festival in Atlanta invited a panel of chefs and recent cookbook authors to discuss their thoughts on soul food and its influences on their cooking. Panelists included chefarmer (chef-farmer) Matthew Raiford, author of Bress ‘n’ Nyam: Gullah Geechee Recipes from a Sixth Generation Farmer. Born and raised on family farmland in Brunswick, Georgia, Raiford left home at age eighteen and served in the military, traveled internationally, and attended culinary school at Hyde Park in New York. When his grandmother handed him and his sister the deed to Gilliard Farms, telling them they needed to get back to farming the land, Raiford picked up the family practice with a commitment to preserving the cultivation and cooking methods of his ancestors.

His cookbook presents these methods and uses them to interpret the legacy of African American cuisine. The Local Palate sat down with Raiford to discuss his perspective on soul food’s past, present, and internationality.

EXPLORING THE EVOLUTION OF SOUL FOOD WITH MATTHEW RAIFORD

The Local Palate: How has your perception of soul food evolved over time?

Matthew Raiford: When I look at soul food, I don’t look at it like a pointed thing—I look at it as foods that people have come to consider as “American,” especially foods in the Southern portion of America. These foods are African ingenuity driven, but they’re a combination of all the people living here.

I like the term “soul food,” but I think it’s associated with a very specific place: the South. But, as you start to move and people start to move, we need to embrace all the different places people ended up in through the Great Migration. In the United States, everyone’s families started on the East Coast, if you were of European or African descent. From there you were pushed farther west. You had to take the foods you knew and apply it to all the places with riffs on “What grows here?” and “what can I get there?”

TLP: What memories do you have of the foods you grew up with, and do those align with how you think of soul food today?

MR: Soul food, Southern food, and the foods of people’s ancestors have totally moved and twisted regardless of where they are. We have to think about food from all the places it’s coming from. You think about soul and things that touch their hearts, they’re all related to women. People talk about “My grandmother’s recipe… My mother’s recipe…”

We need to start embracing more women because they were our providers, and back in the day, women weren’t allowed to have major jobs because they were homemakers. Shelling peas, peeling fava beans, making pasta were part of their daily thing. When we look at where food was and where we are now, there’s a massive number of women part of this push. When we think about soul food, we need to think about our mothers, our grandmothers, our great grandmothers who passed down these recipes.

TLP: What got you into the kitchen?

MR: As a kid, I wanted to emulate my dad. He was a baker by trade. I grew up eating laminated dough apple turnovers where he’d laminate the dough the night before and stewed the apples. I knew what petit fours were when I was six; I knew what laminated butter was when I was four. Because he was who he was, he wasn’t allowed to go work anywhere in the South doing these things he learned up North, so he worked at the Lewis Crab Factory.

I grew up around that, and my mom was a very decent cook. Any of the recipes you see in [Bress ‘n’ Nyam] that say “Effie’s” is my mom’s that she passed down to me. The molasses pound cake, for example, was because we didn’t have any white sugar in the house, but she had brown sugar and she goes, “Oh, I know how to do this.”

Looking at food from those perspectives made me want to cook. But in the 1960s, my dad didn’t want me to cook. At that time, he’d never seen an African American holding chef positions in the kitchen. They were always called “cooks,” never “chefs.”

When I joined the military and got to Germany, the guys found out I was from Georgia, and they said, “Man, I haven’t had a home-cooked meal in so long!” They equated the fact that I was from Georgia that, well, I must know how to cook. It’s really interesting that these people weren’t from Georgia—but from Chicago, Philadelphia, Texas—but they equated their home-cooked meals to greens, barbecue, and roasted meats.

Now, cooking is like therapy for me now. Southern cooking is about repetition that’s always the same and always feels like home. For lack of better words, it’s a virtual hug every time you eat.

TLP: What elements of other nations’ cuisines did you fall in love with as you’ve traveled? Did you discover any culinary traditions that resonate with your notions of soul food?

MR: I love the pickling and fermentation aspect of Asia, especially Korea. Long fermentation develops flavors from kimchi to peppers, and it’s amazing. The connection to other cultures made me realize we’re more the same than we are different. All these cuisines that we consider haute cuisine started as peasant food. We’re more alike in wanting to be soulful in what we present to each other and what we enjoy.

share

trending content

-

9 Noteworthy Tennessee Restaurants

by Margaret Littman -

Outdoor Adventure and Historic Charm Awaits in St. Martin Parish

by TLP's Partners -

6 Things to Do Beyond Golf in Pinehurst

by TLP's Partners -

Charlottesville, Virginia Named Wine Region of the Year

-

A New Home for Lazy Betty

by Lia Picard

More From In the Field

-

From Pop-Up To Brick-and-Mortar

-

The Return of the Lynnhaven Oyster | Listen

-

What’s On the Horizon for 2024

-

Sorelle: La Dolce Vita in Vogue

-

Keya and Co. Turning Sadness into Sugar