Join the Cookbook Club

Members Only Content

This page is for Cookbook Club members only.

If you are a member, please sign in and try again.

If you are not a member, click the button below to sign up.

share

Related

-

A Cajun Christmas Menu

by TLP Editors -

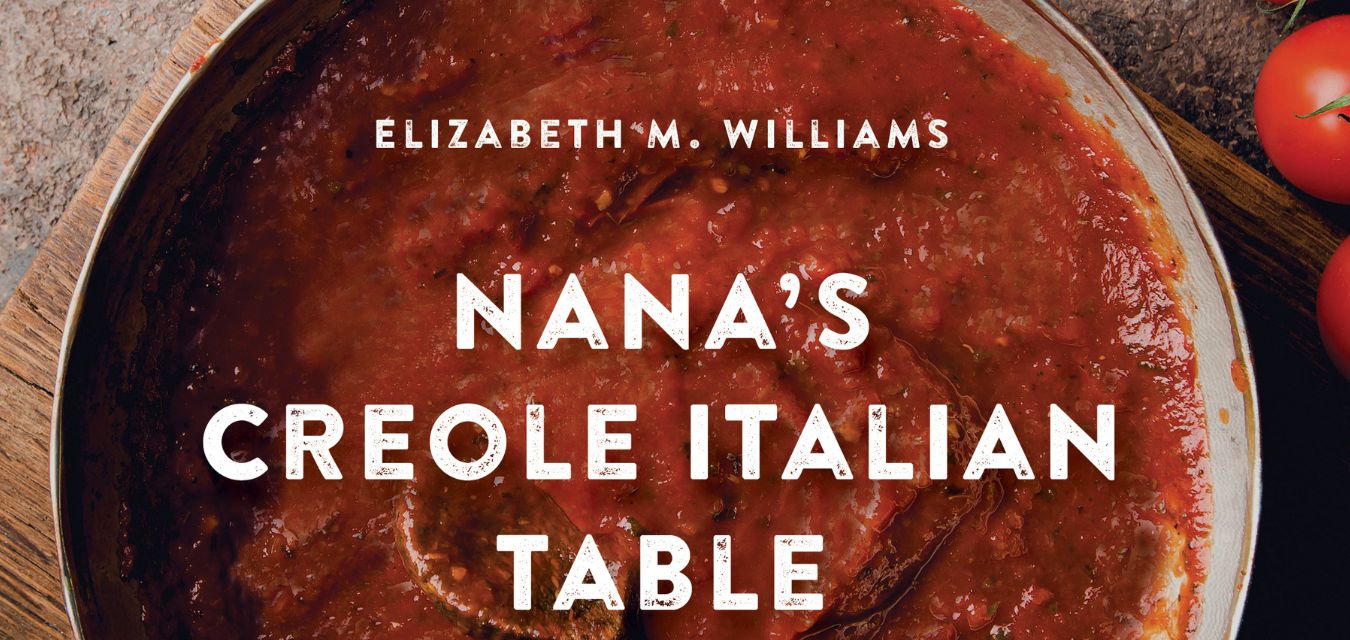

A Crescent City Icon, Reimagined

by TLP Editors -

The Challenges in Louisiana’s Bayou

more from Cookbook Club

-

7 Cookbooks All About Barbecue | Listen

-

Cookbook Review: Sweet Potato Soul | Listen

-

Q&A with Lucian Books & Wine | Listen

-

9 Cookbooks from Black Chefs to Celebrate Juneteenth | Listen

-

4 Cookbook Stores To Fill Your Mind and Plate | Listen