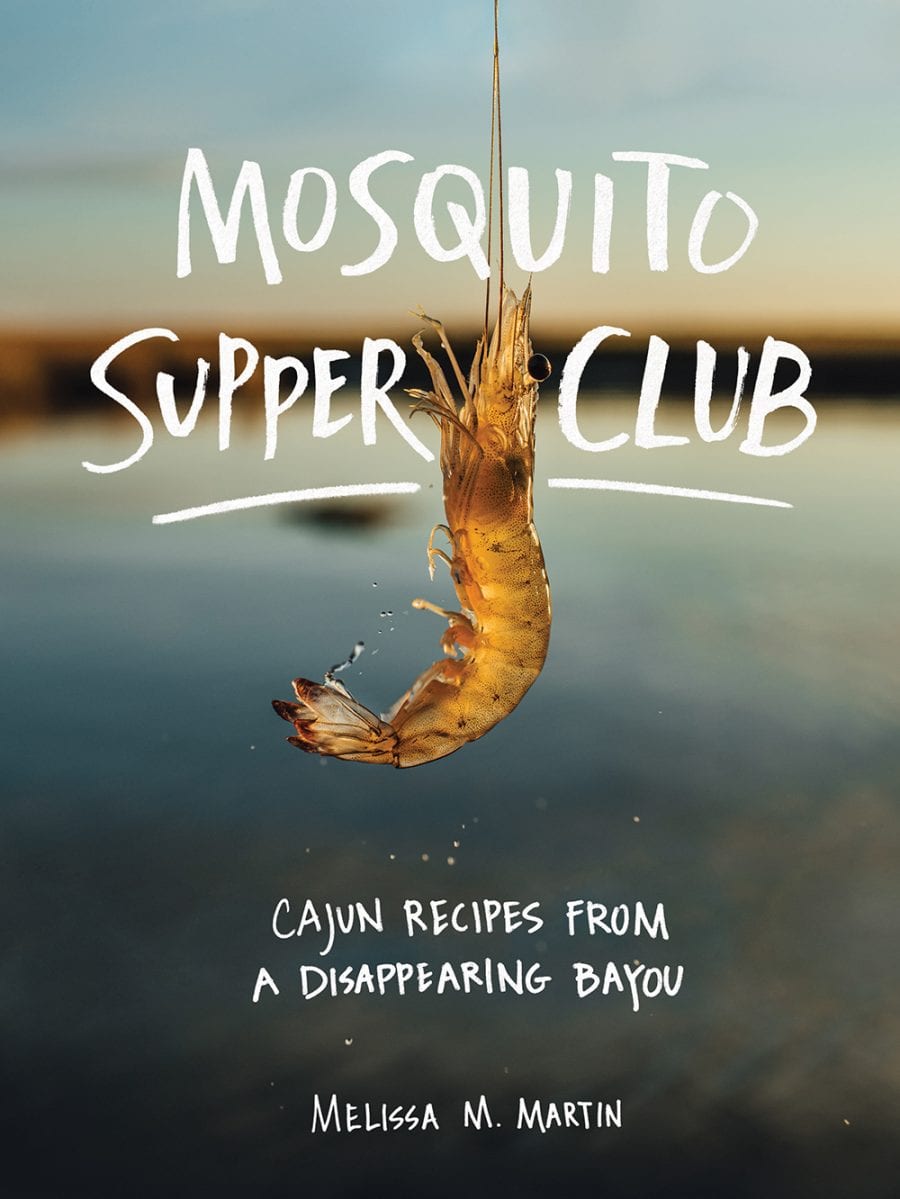

In her new cookbook, Mosquito Supper Club, Melissa Martin pays homage to the vanishing South Louisiana community she calls home

The first thing I think when someone refers to the states below the Mason-Dixon Line is “that’s the North.” As a child in one of the southernmost parts of Louisiana, I didn’t understand the concept of the American South. To me, everything above Baton Rouge was the North. I grew up with leftover gumbo in the fridge and an oil rig drilling just outside my window. I didn’t know it was special to eat cold crabs for breakfast and be surrounded by water and bayous, ibis and pelicans, receding land and dying cypress trees. I also didn’t know I was Cajun.

I was born and raised in South Louisiana in Terrebonne Parish. Terre bonne means “good earth” in French, and situated as it is on delta soil, the parish is aptly named. The Terrebonne my dad remembers growing up in sounds like a fairytale land: cypress-and oak-lined waterways; squirrels jumping from tree to tree overhead; egrets, cranes, and herons hiding in hues of green, blue, and emerald.

Now the 100 million migratory birds that use South Louisiana as a wintering habitat lack landing pads in Terrebonne Parish. Most of the cypress and oak trees that are still standing are stripped to bare branches, and the majority of the islands and bayous that encompassed the barrier waters have become lakes. Terrebonne Parish is hanging on to the coastline for dear life. Louisiana is losing more good earth than any other place on the planet. The coast, a thick, ever-changing blanket of marsh, is disappearing, and our wetlands and bayous along with it. A whole list of places in South Louisiana that once held history are now covered in water. Before Cocodrie and Chauvin—the lands on which my grandparents, parents, siblings, and I were born and raised—join that list, I want to make sure we put the Cajun food I grew up with and the people responsible for it on record. It’s imperative that the small fishing villages that push out so much seafood, tradition, and culture be remembered before time and tides take their toll.

It is time to recognize the problem and the risk: When this land disappears, it takes with it a portion of our nation’s safety and food supply, and a long legacy of culture and traditions. If we narrow our focus from the world to North America, then to Louisiana, then to the state’s tiny bayou parishes, we can illustrate a universal threat to communities bound by culture and tradition. A tradition paying homage to fishermen, farmers, hunters, and trappers.

To be Cajun is to be so many things. I tell the stories in my book to recognize the challenges and to shine a light on all that is good. And to lead a call to every one of us to recognize that our environment is in dire straits, and in South Louisiana, our homes and Cajun culture are at risk of another expulsion. We must learn from the past and recognize how it shaped us. This cookbook is how I distilled my life as a Cajun woman and how I choose to tell it. After all, the best part of life is our stories and how we pass them on.

Lucien’s Shrimp Spaghetti

Shrimp spaghetti is to bayou kids what spaghetti and meatballs is to kids in the rest of the United States. This was my son Lucien’s favorite meal, which he would eat for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. It’s a near perfect meal—simple, sweet, balanced—and it’ll feed a big family or a crowd of friends. The recipe draws from the Creole cooking technique of smothering tomatoes long and slow. This version is made with store-bought canned tomato sauce, but you can certainly make your own tomato sauce and cook it down in the same manner. Homemade tomato sauce tends to be thinner, so you might have to thicken it a bit with tomato paste to get the right consistency.

Velma Marie’s Oyster Soup

My mom gave me my grandmother’s Magnalite soup pot when I was going through a rough time; seeing it daily helped ground me in my life’s work: procuring ingredients and cooking. It is the pot my grandmother cooked her oyster soup in, a memento of a life lived. The battered pot reminds me of her patience and kindness, her wit and fierceness, and her ability to marry ingredients. Her grandfather, father, and husband were oyster fishermen. This is a soup to feed a large family and hungry workers.

It is a fishermen’s soup and, for me, a prayer. My grandmother’s oyster soup tastes of salt pork and briny oysters, of sweet tomatoes and alliums. Like the mussel and fish stews of France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, it marries tomatoes and seafood in a broth. It resembles a tomato-forward bouillabaisse and smells like the oyster beds of Louisiana. The pork comes from our Acadian salt- curing roots; it mellows the acidity of the tomatoes and mingles perfectly with the salt from the sea.

The soup’s taste is also dependent onthe oysters’ liquor, so you really want to procure as much as you can. The best way to do this is to shuck your own oysters and reserve all the drops of liquor from the shells, or ask a seafood purveyor to save you the precious liquid. If you can’t shuck your own, then forge ahead with fish or chicken stock. It’s important to hold off on salting the soup until the very end, as the pork and oysters pack loads of salt.

Crab Claws in Drawn Butter

Ask your fishmonger for cracked crab fingers, or if you’re having a crab boil, put some of the crab claws away. The crab finger, or claw, is the large pincer with the shell removed around the meat and the pincer still attached so you can hold on to it while sliding the crabmeat off through your teeth.

share

trending content

-

Outdoor Adventure and Historic Charm Awaits in St. Martin Parish

by TLP's Partners -

6 Things to Do Beyond Golf in Pinehurst

by TLP's Partners -

Charlottesville, Virginia Named Wine Region of the Year

-

A New Home for Lazy Betty

by Lia Picard -

Will Travel for Southern Food

by TLP Editors

More From Roots

-

The Pakalachian Food Truck Blends Traditions | Listen

-

Treasuring Time at the Table at a’Verde

-

Remembering Malinda Russell through her Recipes

-

Ricky Moore’s Juneteenth Lunchboxes

-

Hamsa: All Roads Lead to Israel