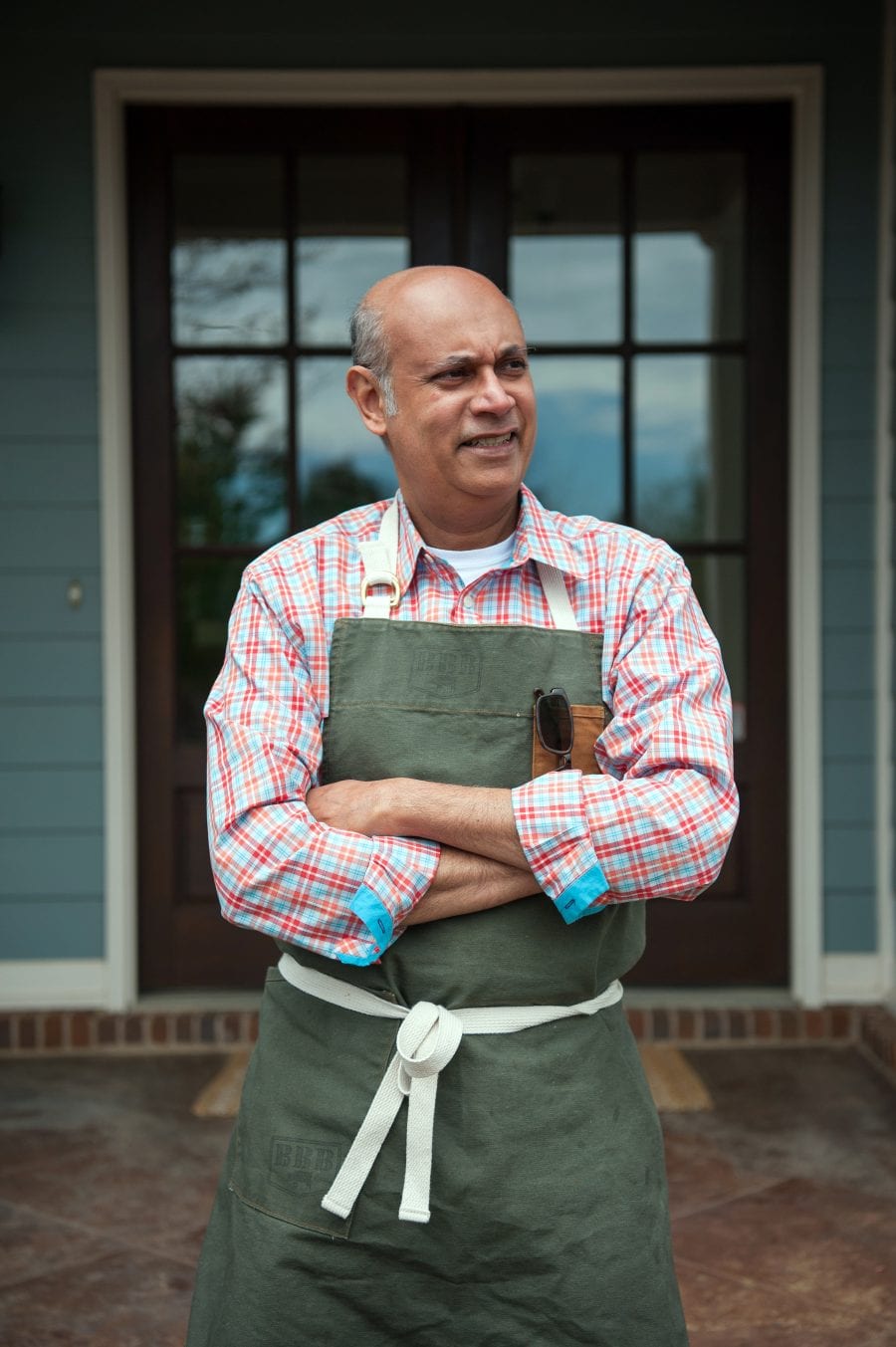

FROM GUJARAT TO MISSISSIPPI, CHEF VISH BHATT’S SOUTHERN JOURNEY

When I think of a Southern brunch, I picture poached eggs doused in hollandaise or smoked meats. But this spring, when I visited Chef Vishwesh Bhatt at his home in Oxford, Mississippi, he offered an unexpected treat. He was standing over a pot full of Sea Island red peas. He’d soaked the peas overnight and let them sit for a few days, so they had developed fledgling sprouts. He offered me a taste before he began to sauté the peas: earthy, I found, with a nutty flavor.

Bhatt is the executive chef at Snackbar, a beloved, dark-paneled bistro in Oxford. The restaurant launched as a mash-up of casual French fare and down-home Mississippi hill country food—a “Bubba brasserie,” as it says on the website. For five years running, Bhatt’s cooking at Snackbar has made him a finalist for the James Beard Foundation’s Best Chef: South award.

I had come to his house for a lesson in cooking peas and beans, which he considers some of the great common denominators of the global pantry. I’d also come to learn his story—which, I discovered, could be said to have begun with a similar dish. “This is something I grew up with,” he told me, gesturing towards the pot of peas. His mother would cook sprouted peas with ginger, mustard seed, and a couple of curry leaves, and serve it for Sunday breakfast—though in Gujarat, India, where he grew up, she used mung beans. Bhatt would help prepare those meals, first just shucking the peas, but taking on more elaborate responsibilities as he grew older. These meals taught him to care for ingredients. “It’s a part of the Hindu philosophy,” he says. “Food is sacred.”

Despite that early exposure, Bhatt had no intentions of staying in the kitchen. He loved birdwatching and thought he might work for the Indian Forest Service. But he was stymied by the country’s dense bureaucracy—and by his own diffidence. By the time he graduated from high school, Bhatt had acquired what he calls a “typical, I-don’t-care-about-this” attitude. His parents, who had gone to college in the United States, thought leaving India might help kickstart their son.

They moved first to Strasbourg, France. Bhatt’s limited French fluency kept him from enrolling in college, so he spent his days wandering the city. Strasbourg, the seat of the European Parliament, is diverse and cosmopolitan. Bhatt befriended fellow immigrants, many from former French colonies—Algeria and Morocco, Mali, and Senegal. For the first time, he began to discover that the world’s cuisines are interconnected by ingredients and flavors. There were differences, too, of course. Bhatt had to abandon his family’s tradition of vegetarianism, common though not universal among Hindus, so that he could sample the full range of his new friends’ foods.

After eleven months in Strasbourg, the family moved to the US. Bhatt enrolled at the University of Kentucky and, inspired in part by his experiences across the world, decided he wanted to be a bureaucrat—a goodhearted and skilled bureaucrat, the sort of person, he figured, who could tackle the problems he saw in the world. In 1992, when he graduated, Bhatt enrolled in a political science program at the University of Mississippi, where his father was teaching physics. Then, once again, his interest in school began to wane.

In college, Bhatt had begun cooking at a diner to earn extra money. He kept cooking in Mississippi, and when he was offered more hours in the kitchen, he took them. His hours in the classroom, meanwhile, dwindled, until grad school fizzled away.

Chef John Currence had also arrived in Oxford in 1992, and opened his first restaurant, City Grocery. Bhatt was impressed with the restaurant, and in 1995 worked up the courage to ask Currence for a job. Bhatt started off prepping ingredients, but it was clear at once that he had found his career. He loved this world of high-end cooking. Its emphasis on professionalism matched the spiritual significance his family had granted to food.

So, in 1998, Bhatt left for culinary school in Miami. He cooked briefly in Colorado, and then at a newly opened restaurant in downtown Jackson, Mississippi. The Black Water Café, as it was called, struggled—the neighborhood wasn’t ready yet. But, as if in exchange for those struggles in Jackson, Bhatt met Teresa, his future wife.

In 2002, unhappy with the way things were going at the cafe, Bhatt came back to Oxford for a few days. His parents were returning to India, and he was helping them pack. He bumped into Currence, who said he was looking for a catering director. Was Bhatt interested? The chef once again changed the vector of Bhatt’s professional life. He stayed with the restaurant group, rising in rank, until he was named chef de cuisine. In 2008, Currence told Bhatt he was planning to open a new restaurant—Snackbar. When it opened in 2009, the two chefs worked side-by-side in the kitchen for a year. Then Currence pulled back, handing Bhatt the reins. That decision has been rewarded. In 2011, Bhatt was named the people’s choice for “Best New Chef” by Food & Wine magazine. Three years later, his long run of Beard nominations began.

Bhatt thinks of his cooking as quite simple. It’s just beans and greens and rice, he told me as he prepared our breakfast. Ingredients he grew up eating; ingredients he still likes to cook at home.

These days, there’s an echo of his childhood meals in Gujarat—catfish might be served atop garam masala succotash, and hoppin’ john comes topped with chaat. In his early years at Snackbar, though, Bhatt rarely used Indian flavors. Part of the change in his cooking, he told me, was the loss of his mother. She passed away just a month before he and Currence conceived of Snackbar. Cooking, he says, offers a link to his childhood.

“As an immigrant, this is what’s left to connect me to where I came from.”

The first time I met Bhatt was at a supper club event in Tunica, Mississippi. The menu featured Southern ingredients retouched with that distinctly Indian flare: the shrimp were saffron-poached and pickled, the catfish fried in chickpea-flour batter. He announced to the diners that all the ingredients had come from within one hundred miles of Tunica, except the spices—which had come from within one hundred miles of Gujarat.

Before the dinner, I spoke with diners who were eager—they knew of Bhatt’s great reputation—but also wary. Hailing from small towns, many had limited exposure to Indian food. Then dinner was served. The man next to me began to repeat a phrase: “This is so strange,” he said. “But good.” It became a mantra. “It’s strange, but good,” he repeated, over and over. Another diner approached Bhatt after the meal and told him that for the first time, she’d enjoyed Indian cooking. Bhatt’s response was polite, but firm: This, he said, was not Indian food.

Over our sprouted-pea breakfast, I asked Bhatt about that response. He seemed reluctant, I noted, to be labeled an Indian chef. “I’ve been here, cooking in the South now, [for] twenty years,” he replied. “I cook with Southern ingredients. For some reason, the things I’m asked to do—” Here he paused. “How can I say this without being rude?” Finally, Bhatt settled on an analogy. Other immigrant traditions have blended into Southern cooking without commentary. Chefs with, say, Scottish heritage, aren’t asked constantly to talk about haggis. So why can’t he just cook what he cooks and leave it at that? To call this food strange is to say that in some way it doesn’t belong, that it’s not a part of the South.

Indian spices have always appeared in the kitchens of the American South, Bhatt added. “Think about something as iconic-Southern as sweet tea. You don’t have that without the tea or sugar—which are both Indian ingredients.” Bhatt thinks food offers a rare place to focus on connections, rather than what sets us apart. “That’s the conversation I want to have,” he said.

Restaurants can be a tough business. In his first years at Snackbar, Bhatt all but lived there, putting in twelve to fourteen-hour days. But now, nine years later, he has developed a strong team, to whom he has handed over many responsibilities. He tries to spend as much of his time as possible at home with Teresa. Sunday mornings are a special time, he says. Which left me worried that I was intruding. Bhatt assured me that this was not the case. “This”—he gestured with his shoulder, encompassing the kitchen—“is fun to me.” He learned in childhood that cooking for others was a pleasure. Food is sacred, after all.

Later, as our meal wrapped up, I glanced at Instagram. Bhatt had shared a photo of the red peas, with their tiny shoots. “Mom taught me how to sprout peas and beans,” he wrote. The dish I ate was a way to take that story, that memory, and put it out into the world.

VISH ON PEAS

Minestra

Savory Black-Eyed Pea Griddle Cake

Sprouted Sea Island Red Peas

Green Lima Beans and Sesame Seed Sauté

Nachomama’s Cornbread

Tomato-Cashew Chutney

share

trending content

-

New Restaurants in Arkansas

-

Shrimp and Grits: A History

by Erin Byers Murray -

Tea Cakes, A Brief History

by TLP Editors -

Gullah Geechee Home Cooking

by Erin Byers Murray -

The History of Fajitas

by TLP Editors

More From In the Field

-

Staff Meal

-

From Pop-Up To Brick-and-Mortar | Listen

-

The Return of the Lynnhaven Oyster | Listen

-

What’s On the Horizon for 2024

-

Sorelle: La Dolce Vita in Vogue