Integrity in Geometry

By all accounts, Jed Curtis was a weird kid. Early on in elementary school, his class visited a living history museum and he became fascinated with the blacksmith, hammering and manipulating molten metal into new shapes. So his parents struck a deal with him: If he could keep from breaking his glasses until Christmas, not an easy feat for a rambunctious young boy, they’d buy him an anvil. He succeeded, and from there, every holiday brought new hammers and different tools as he experimented making his own objects out of metal. Still, he never thought about metalwork as a career—he didn’t want to fall into a starving artist trope. But after earning a degree in chemistry from Roanoke College and getting engaged to then-girlfriend Hannah, he decided it was now or never.

“We had no kids and no mortgage,” he says. “I could go out and get a ‘real’ job, or I could take the opportunity and jump in.” He started in architectural metalwork, making railings and the like, but there wasn’t a market for things he wanted to create. In a world where most building pieces are premade and assembled, Curtis is a rare person who wants to take raw materials and make something beautiful. But inspiration came, as it often does, by way of a trip to Target.

The couple needed a new skillet. Both had grown up cooking with cast-iron and weren’t fans of non-stick (or contributing to landfills with flimsy products). “I like old stuff that you become the steward of,” he says. “You’re not a consumer, you’re an owner. Like the way shoes break into your foot shape—you have a connection to it.” Curtis went out looking for a new skillet and didn’t like what he saw on the shelves. “They were all easy to manufacture, but there was no reverence for the material,” he says. Instead, he went home and decided to make his own.

He got to work making the best skillet he could with a surface perfect for seasoning. The end result was mind-blowing, he says. When he knew he was onto something, he gave one to a chef friend, who said it was better than the commercial ones they used. In particular, Curtis’ skillets are heavier than traditional cast-iron pans, which make them better for heat retention. He likens it to horsepower: “If you don’t know how to drive it, you’ll wreck. But once you get the feel for it, it’ll go forever.”

Today, Curtis runs a solo operation called Heart & Spade forge, making skillets of all sizes to ship across the country as well as for a handful of restaurants, including Roanoke’s own River & Rail and Breadcraft. “I’m the only one that makes them. It slows things down, but ensures quality and consideration,” he says, noting the three-month lead time for orders. Each skillet takes between ten and twelve hours to make from start to finish. “Each one is ever so slightly different, like different pages of the same book,” Curtis says. Sizes run from six inches to a whopping twenty-inch, and he makes a few different styles: The bakers are deeper and have shorter handles than traditional skillets, while the griddles are heftier with lower walls for steam evaporation—great for searing meats.

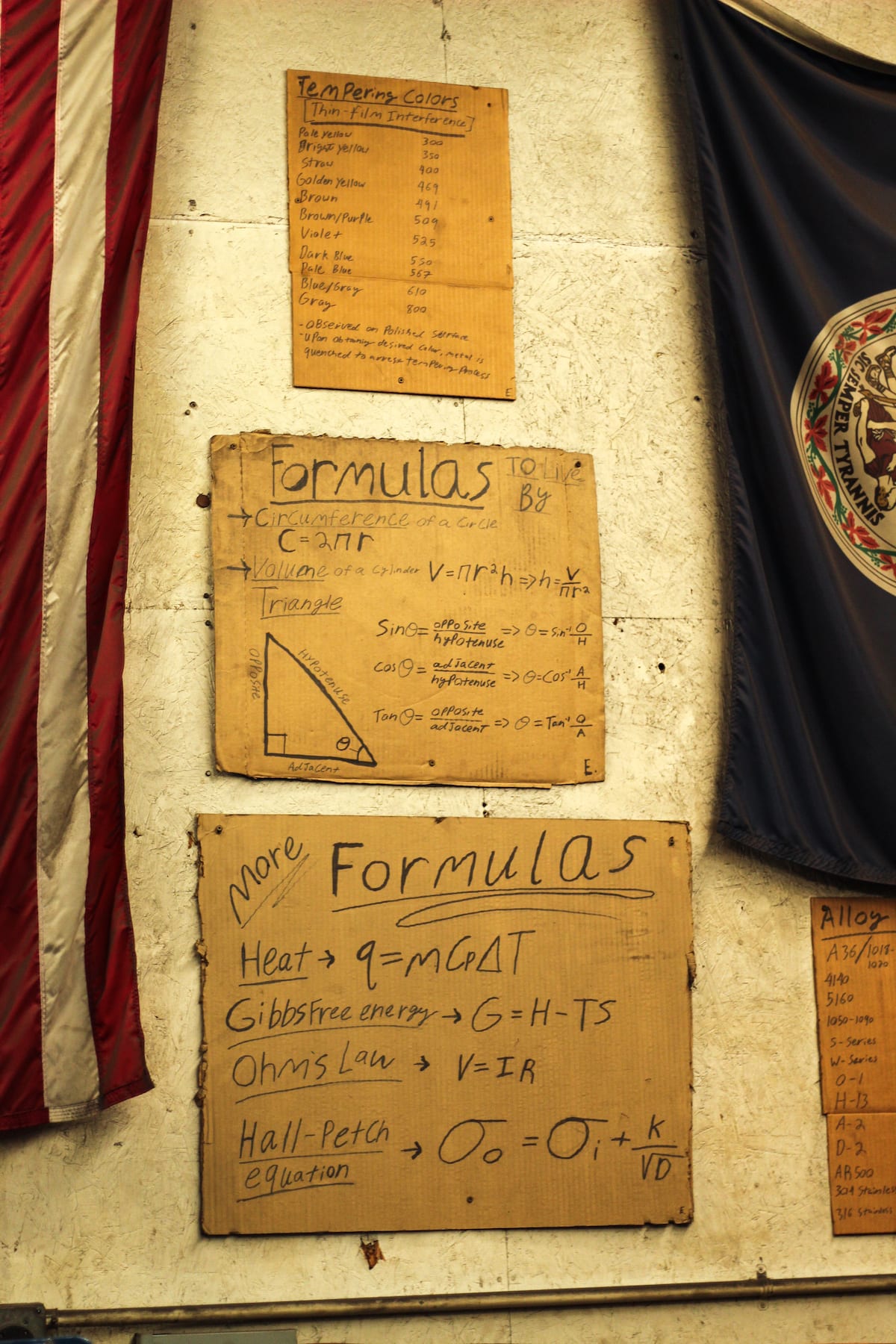

Forging is a manipulation of volume, Curtis explains. You’re not adding or removing, just moving the material around. As opposed to casting, which he says relies on the alloy of the metal, forging relies on the science and density of the steel. He’s plastered the walls of his shop with scientific equations for density and mass, forms that indicate why steel is the best for heat transfer, and formulas that explain the relationship between temperature and pressure—and the point where they coexist. “My unique weirdness is that cookware is my point where art, craft, and science coexist,” he says. “The weight, proportions for handles—it’s all putting theory into practice. There’s integrity in geometry.” At the end of the day, this is a Roanoke operation through and through. “Roanoke is a chip on your shoulder. We have this rich industrial heritage in steel and steam locomotives,” he says. The construction of Curtis’ skillet handles are inspired by the rivets on boilers from steam locomotives—designs he found in old industrial journals.

But Curtis isn’t designing skillets for the past. “I’m not even building it for you. It’s for the historian who finds it in your house in 200 years.” Many of his orders are gifts, and he offers engraving as an option. “I love to include the date. You just know it’s something the grandkids will fight over—grandma and grandpa’s anniversary skillet.”

For more on the science of seasoning your skillet, subscribe to our digital edition here.

share

trending content

-

Chefs Heading To The Palmetto Party

by TLP's Partners -

A First Look at Fancypants | Listen

by Erin Byers Murray -

How to Build the Perfect Cheese Board | Video

by Maggie Ward -

5 Things to Do in Bath County, Virginia

by TLP's Partners -

Bearing Fruit at Big Apple Inn

by Erin Byers Murray

More From In the Field

-

What’s Good in the Neighborhood | Listen

-

10 Southern Innovators Changing the Game

-

Why Aren’t We Eating More Wild-Caught Shrimp? | Listen

-

In the Kitchen with Chef EJ Lagasse of Emeril’s | Listen

-

Playing With Fire at Austin’s Best Food and Music Festival | Listen