Southern Black chefs embrace a centuries-long history of veganism and vegetarianism within their communities

The African-American relationship with veganism may seem like a trend in recent years, but that is far from the case. In fact, there’s a longstanding legacy of plant-based meals in the Black community. Only recently have we seen a significant increase. As more Black Southern chefs begin to cook with plant-based diets in mind, they are continuing a dietary tradition that honors a heritage stretching back at least hundreds of years. And in the process, they are introducing new generations to a healthier lifestyle steeped in history.

Today, even a casual search for vegan restaurants and food trucks will uncover more options than ever. Often, Black chefs are at the helm finding innovative ways to create dishes that appeal to vegetarians and meat eaters. According to a 2016 Pew Research Center survey, 8 percent of African-American adults are vegan, in comparison to 3 percent of American adults overall. However, this is not a recent fad. In fact, the plant-based diet has deep roots in West Africa. But when Africans were brought to America and enslaved, they had to adapt their diet to what was available.

Dr. Frederick Douglass Opie wrote in his book, Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America (Columbia University Press, 2010), that while the traditional West African diet did contain meat, it largely consisted of “darker whole grains, dark green leafy vegetables, and colorful fruits and nuts […] The African and Amerindian diets contained far more vegetables and legumes than the Europeans consumed.”

Once in America, when allowed, enslaved people grew gardens to help supplement their diet. Author Michael W. Twitty described the gardens in his book The Cooking Gene (Amistad, 2017), as “little landscapes of resistance: Resistance against a culture of dehumanizing poverty and want, resistance against the erasure of African culture practices.”

Religion also played a central role in African Americans deciding to choose a plant-based diet. Seventh-day Adventists, a Protestant offshoot that opened membership to African Americans in the 1800s, promotes a vegetarian and kosher lifestyle. Members of the Nation of Islam are also vegetarian. Elijah Muhammed, a former leader, wrote two volumes on plant-based eating. How to Eat to Live (Secretarius MEMPS Ministries, 1962) outlined the correlation between eating and mental and spiritual health. In the book he notes, “We are, by nature, vegetable-and fruit-eating people.” Muhammed encouraged members to stop eating soul food, noting that modern-day food did not contain healthy nutrients.

Taking Care of our Bodies

Vegetarianism also has links to Black social activism. Perhaps the best example is through comedian and civil rights leader Dick Gregory. In his book, Dick Gregory’s Natural Diet for Folks Who Eat: Cookin’ with Mother Nature (Harper Collins, 1974), he wrote, “the philosophy of nonviolence, which I learned from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. during my involvement in the civil rights movement was first responsible for my change in diet.”

In another book, Dick Gregory’s Political Primer (1972), he explained, “…when Americans become truly concerned with the purity of the food that enters their own personal systems, when they learn to eat properly, we can expect to see profound changes effected in the social and political system in this nation. The two systems are inseparable.”

Bryant Terry, chef, publisher, and author of Afro-Vegan (Ten Speed Press, 2014), Vegetable Kingdom (2020), Vegan Soul Kitchen (Da Capo Lifelong Books, 2009), and Inspired Vegan (2012) cites Dick Gregory as an influence. “I’m standing on the shoulders of these ancestors. It’s important for people like me to carry the torch of the elders, like Edna Lewis and her focus on seasonal and local traditions. They inspired me to uplift our food and our traditions,” Terry says. “But the biggest inspiration for me was hearing the song ‘Beef,’ by KRS-One and Boogie Down Productions. KRS-One always peppered songs with lyrics [about] what we’re eating. Going beyond personal health, he was tackling our industrialized food system and getting at the way animal agriculture can affect human health.” Ultimately, the combination of Gregory and KRS-One started Terry on his own journey to veganism.

Black Veganism in Action

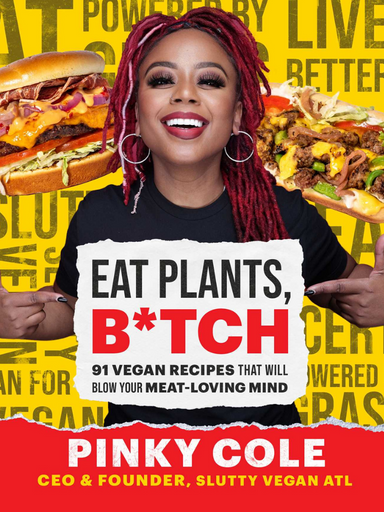

Several Southern Black entrepreneurs are not only choosing vegetarianism, they’re opening restaurants and food trucks to spread plant-based dishes to the masses. One of the most notable restaurateurs is Pinky Cole, CEO and founder of Slutty Vegan ATL in Atlanta. Slutty Vegan started in Cole’s apartment in 2018, when she began taking orders via Instagram. Shortly after, she started selling plant-based burgers from a food truck.

A brick-and-mortar location opened later that year and several locations have followed, making it a destination for locals and tourists. “We have people lined down the block every single day. That tells me that obviously we’re doing something right, and we’re having an impact in the South,” Cole says. “My core audience is meat-eaters. I’m intentional about that. Vegans have already made the conscious decision not to eat meat, but the meat eaters are the people who I really want to speak to. We strive to make veganism fun and accessible.”

Menu items are a nod to the playfulness that Cole wants to convey and what she calls the “orgasmic” experience she wants diners to have while eating. For example, the One Night Stand is a plant-based patty with vegan bacon, vegan cheese, caramelized onions, lettuce, tomato, and “Slut Sauce” on a vegan hawaiian bun. The Side Heaux is made up of fried vegan shrimp tossed in buffalo sauce and served with fries, coleslaw, and housemade ranch sauce.

It was important to Cole to raise awareness of the effects diet can have, particularly when it comes to heart disease and type 2 diabetes in the Black community. But it was also important to show the breadth of what a plant-based diet can be. “Veganism is not just kale and quinoa salads,” she says. “Healthy eating means eating what makes you feel good! We know that vegetables and quinoa are a big part of most vegans’ diets, but who says you can’t enjoy a great burger every now and again too?” This fall, Cole has a cookbook coming out, Eat Plants, B*itch: 91 Vegan Recipes That Will Blow Your Meat-Loving Mind (Gallery13a, 2022). Recipes span from avocado egg rolls to black pea cauliflower po’boys.

Ethics of Black Veganism

Although health is a reason many people decide to change their diets, so is animal cruelty. Mariah Ragland, owner of the pop-up Radical Rabbit in Nashville, watched the movie 12 Years a Slave while attending Fisk University. She saw similarities in the treatment of the enslaved characters and animals. Ragland started Students for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and volunteered at an animal shelter. “Then [activist and author] Angela Davis came to campus and talked and said what I felt,” Ragland says. “She said something like she was vegan because back in the day we were chained and nowadays we chain animals.”

At Ragland’s pop-ups, she takes fairly typical dishes, such as ribs, macaroni and cheese, and egg rolls, and reinterprets them with vegan ingredients. It’s crucial, she says, that everything is “seasoned and full of flavor. Our food is highly flavored. That alone already makes a difference from some other vegan dishes, and the movement is really growing in the Black community.”

David Richardson, owner of The Dirty V food truck in Columbia, South Carolina, believes that giving people a wide range of options is key, regardless of whether or not they are vegetarians.

“About 60 percent of my followers are meat eaters,” Richardson says. “My hashtag is ‘everybody deserves a cheat day.’ For vegans, you can come to me. For someone new [to vegetarianism], they may say, ‘I don’t want a salad or rabbit food.’ There’s no rabbit food on here.”

The key to getting meat eaters to not only try Richardson’s dishes but also become repeat customers is seasoning. He takes traditional soul food items and replicates them in innovative ways without using meat. Collard greens are transformed into collard green egg rolls, and he infuses them with a smoky flavor without using pork. It’s one of his best sellers. “Food is based on taste and seasoning. If you don’t season food right, no one is going to want to eat it.”

This Movement is Here to Stay

Terry has a somewhat different approach. “I don’t like that term ‘soul food’ even though I have used it in my work, even up until recently. I help people reimagine soul food. It’s not big, flavored meats, overcooked veggies, and super sweet desserts,” he says. “When I think about my grandparents, and the type of urban farm that they had in the backyard—fruit, raising chickens, dark leafy greens. Black elders have been doing this—sautéed sugar snap peas, collards that didn’t cook for hours. Is that not Black food? That’s just as Black as ribs or mac and cheese.”

Although there are different approaches to veganism in the Black community, the one thread that connects the chefs is their effort to make sure seasoning and flavors feel familiar, even when meat and non-vegan ingredients aren’t included. Perhaps more importantly, Black chefs are reclaiming the legacy of plant-based eating—and ensuring that the next generation will feel included in the veganism conversation.

share

More

-

Five Classic Atlanta Restaurants

by Jennifer Zyman -

New Restaurants in Georgia

by Lia Grabowski -

New Restaurants in Arkansas

by Kevin Shalin -

New Restaurants In Louisiana

by Local Palate -

Our picks in the Triangle

by TLP Editors

More In the Field

-

From Pop-Up To Brick-and-Mortar

-

The Return of the Lynnhaven Oyster | Listen

-

What’s On the Horizon for 2024

-

Sorelle: La Dolce Vita in Vogue

-

Keya and Co. Turning Sadness into Sugar

Comment 1

Great article.