In the hills of East Tennessee, Allan Benton’s hand-rubbed, smokehouse-cured pork products reign supreme

Stand on the back deck of Allan Benton’s home in Madisonville, Tennessee, and you’ll see the gray haze that gives the Great Smoky Mountains in the distance their name. But down in his basement, it’s the scent of smoke you’ll find coming from the ham and bacon maker’s favorite leather chair.

It’s his spot to unwind after working all day at his smokehouse following dinner with his wife, Sharon (the cook in the family), and after greeting his scrappy squirrel-hunting dog Jackson.

Not that Mr. Benton gets much time to unwind or squirrel hunt these days.

The Prince of Pork stays busy year-round with just twelve employees in his “hole-in-the-wall” operation, as he calls it, to keep up with demand for his product in BLTs, bourbon cocktails, and in dishes served on white linen from San Francisco to New York City. He keeps the fire stoked at the ham house seven days a week, and he’s had only seven vacations in forty years, during which time he’s become a culinary star. Introducing Mr. Benton to a room full of chefs would be like introducing Ralph Stanley to a room full of banjo pickers. Jaws would drop. People would whisper in reverence. But after one conversation, they would know he’s as down-home as one of Stanley’s songs.

Regardless of the accolades and busy schedule, Mr. Benton, who is sixty-six, continues to keep his family customs first.

“We have strong traditions,” Sharon says. “And I think my whole family appreciates that.”

These traditions include ramp hunting in the spring and homegrown tomatoes on the table in summer. But when a nip hits the air, it means pork more than ever.

“I’m just like lots of other people in the South,” Mr. Benton says. “When the weather starts to cool down, I start to crave pork.”

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

When Allan Benton tells a story, his blue eyes twinkle and his cheeks rise up like round dumplings. He sometimes shifts his weight onto one foot before he begins as if to say, “Are you ready for this?” Also like many Southerners, Benton knows how to spin a yarn, and you get the feeling that stories about his grandparents rank as favorites.

“Both my grandmothers cooked on wood cook stoves,” he says. “They preserved everything they had to eat or they raised it. They raised lots of vegetables. They would dry their own pinto beans. It was subsistence living in the purest form.”

Benton’s grandparents lived in a remote area about three hours from Madisonville just over the edge of Virginia. His ancestors had homesteaded adjoining sections, and his mother, Gerri Benton, grew up in a log house—the first ever built in Scott County by white settlers, according to Benton. “The old house that I was born in still stands. The old log smoke house still sits out the back door. It’s probably about a hundred and ninety years old.”

Benton visited his grandparents every year as a child, and in the spring, he woke to the smell of fried chicken to feed about forty. Pork made the table in the fall after the family butchered their hogs.

“Both sides of my family lived a mile apart. Hog killing day was traditionally Thanksgiving Day in those mountains. All day Thursday and Friday and Saturday we would be working up that fresh pork.”

They turned a hand grinder to make sausage that they stuffed into old feed sack. They canned the pork loin, backbones, and ribs and anything else that couldn’t be preserved by curing.

“We didn’t waste anything on that pig that could be eaten,” he said. “The feet, the tongue, the brain, the heart…ears, snout.”

Benton recalls his grandmother making souse meat with the head parts that she would pack into an old crock, cover with a dishcloth, and simply keep on the floor. The old home built on stone held a cool enough temperature to sustain the meat that they would cut off for sandwiches or stack on a cracker. “It might last two or three weeks sitting there,” he says.

And though the days of killing hogs at home have passed in the Benton family, he still gathers the younger generations for traditional meals around pork—the Wednesday before Thanksgiving at his mother’s and Thanksgiving lunch at Sharon’s mother’s. The group might include Benton’s daughters, Elizabeth and Suzanne, his son, Darrell, their spouses, and granddaughters Emma and Avery.

As the Benton family began creating their own traditions, Mr. Benton looked for a ham that tasted like his grandmother’s. He finally got around to asking her to explain the process when she was about ninety years old.

Wash the cure off after two weeks, she told him. Hang it in the smokehouse just for a bit. “We baked that, and it tasted like what I had as a kid,” he says.

Not long after that experiment, chef John Fleer, while at Blackberry Farm, wanted to prepare one of Benton’s hams for guests. It wasn’t a country ham, per se, so Fleer asked Benton what he called it.

“It’s a holiday ham,” he remembers calling it off the cuff. “And it’s been a ‘holiday ham’ since that day. I sell it to several chefs.”

HARD ROE TO HOE

Allan Benton’s relationship with chefs did not come easily or overnight. “The first twenty to twenty-five years I was in business was a real struggle,” he says.

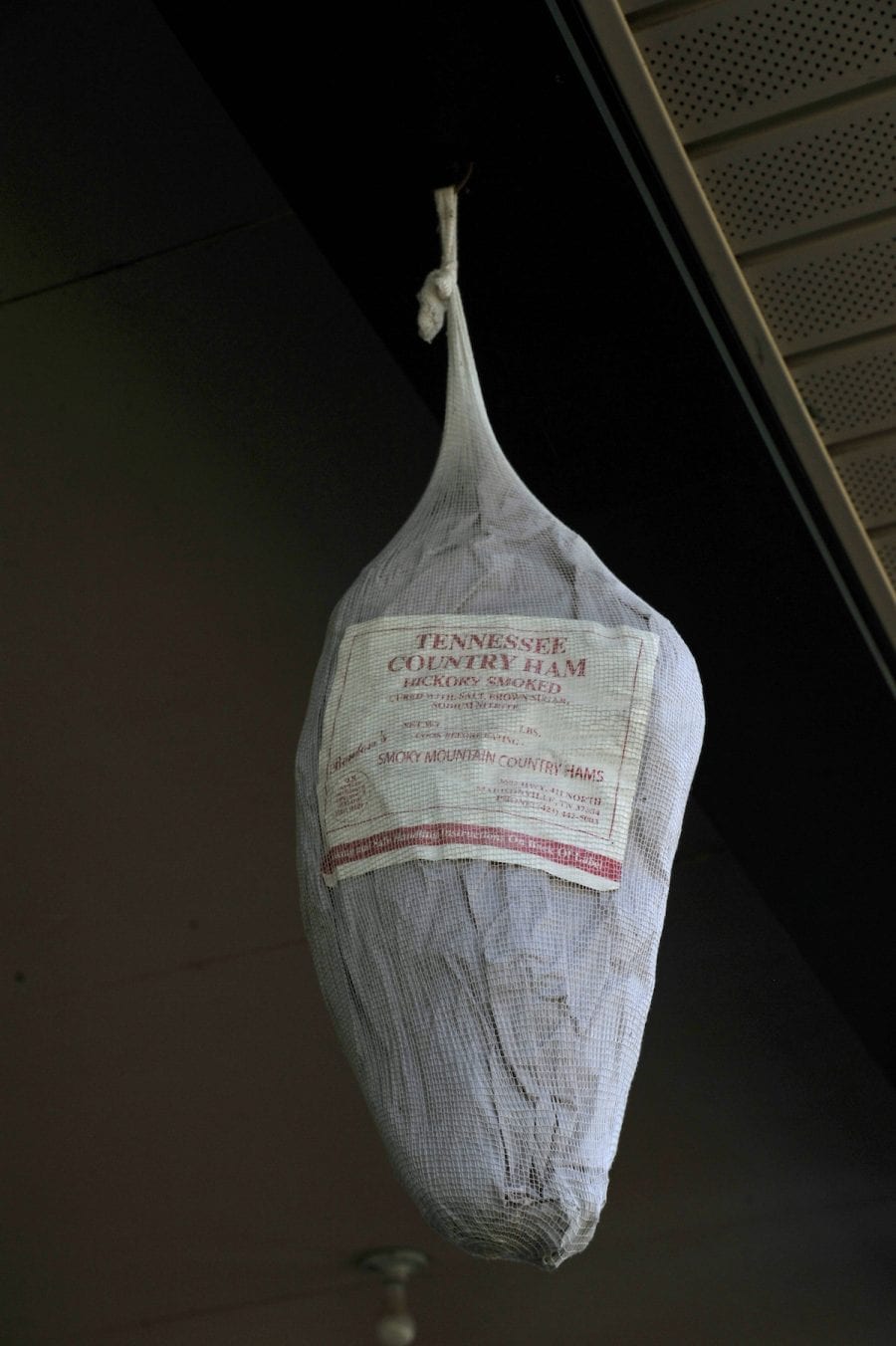

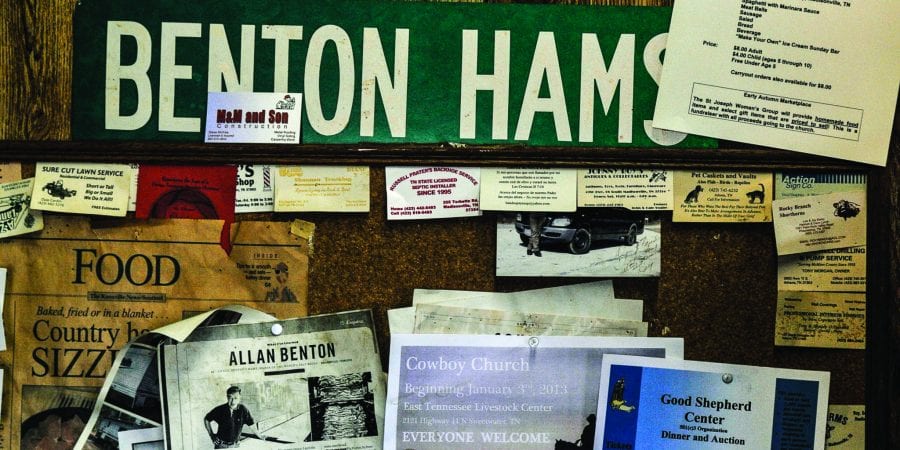

Built from simple cinder blocks, the ham house greets guests with the husky scent of smoke at the front door. Yellowed newspaper articles hang from paneled walls, and a Coke machine still drops sodas for thirty cents. From a glass case out front, Benton stacks jars of chow chow and farm-fresh eggs that he buys for $1.75 and sells for $1.75. (He says he wants customers to experience the difference from supermarket eggs.)

A regular group of locals wander in daily and sit on what Benton calls the “Liar’s Bench” to talk hunting, fishing, and politics. Back when business trickled in, Benton’s father cooked fried chicken or chicken livers on an electric skillet nearly every day. “We’d have twenty-five to thirty people who ‘happened by’ at lunch.”

Beyond cooking for customers, his father gave him some early key advice. Benton had been in business just a few years, and he was barely making it. His eighteen-month and fourteen-month hams sold at the same price you could purchase eighty-day hams elsewhere. “I told my father I might have to quick-cure these hams in order to survive,” he says. “And my dad sat there for a few minutes, and he said, ‘Well, son, if you play the other guy’s game you always lose. If you’re gonna do this, make them the best you know how. And sooner or later, quality will sustain your business.’”

Benton’s father died in 1995 before he enjoyed his current level of success, but the advice on quality lives on today.

“You can’t do it just about right. You’ve got to do it right,” he says. “You want to refine your skills to the point that you believe you’re making it the best you know how.”

That’s part of why the Bentons have high regard for Cruze Farm buttermilk and Anson Mills grains. Sharon even tells about panicking when she ran out of buttermilk over a holiday. She banned her husband temporarily from drinking it straight.

And the ham maker respects the careful way chefs incorporate his product.

“It’s just what the poor Appalachians in this area subsisted on,” he says of the ham that he simply fries up in a pan. Sharon, too, keeps it simple.

“I don’t really cook fancy. I’m just a normal, pretty simple country cook,” she says.

Benton, meanwhile, still forages for ramps. He makes muscadine wine from grapes he grows. And up until just a few years ago, he had rarely tasted the more elaborate creations of his clients in faraway locales. He had never even visited New York City. “I’d never really wanted to,” he says.

But Southern Foodways Alliance director John T. Edge, who along with chef John Fleer helped Benton gain national recognition, convinced him to take a tour of restaurants like Momofuku and Craft where, for example, he tasted a bacon consommé with scallops.

“I have to tell you,” Benton says of the trip, “I loved it.”

In addition to quality, Sharon notes that part of what makes his business a success is his hands-on commitment at the shop every day.

“I always told my three kids, there will always be people in the world smarter than you, you just have to outwork ’em.”

To bring that point home he taught by example. Darrell remembers his father showing him how to rub cure on a ham at age four. All the children made hams of their own, tagged them with their names, and hung them up for customers to buy. Their father would call them down to the shop when they had a taker.

“I thought that was fantastic to sell my ham,” Elizabeth says.

The children all worked in the business eventually. Benton’s eldest, Suzanne, filled orders as early as fourth grade. But Darrell notes that it came with special challenges.

“It’s all fun and games until you’re sixteen and trying to go on dates,” he jokes about the smoke that seeps into clothing. Now at thirty, the family reputation lingers in a different way. He tells of being paged at the Knoxville hospital where he works as a resident in radiology. A fan wanted a favor: “Can you sign a pack of bacon?”

As his father seeks to slow down his pace, Darrell has expressed interest in spending more time at the ham house. “It’s in my blood,” he says. “Fall and winter comes around and I feel like I need to be here.”

To hear Allan Benton tell it, the hard work will be worth it even if it does leave a bit of smoke on your sweater—or leather chair.

“If I had been motivated by money, I would have chosen something else. But I don’t think I would have enjoyed it as much,” he says. “I feel truly blessed.”

WHEN PIGS FLY

When Allan Benton started his business, he could not have foreseen the success and breadth of his products that remain in high demand by top chefs across the country. Holiday orders keep Benton very busy indeed. Here are a few examples of how Benton’s ham, prosciutto, sausage, and bacon are used by America’s esteemed eateries nationwide. To order: bentonscountryhams2.com

Cook with Benton’s

Caramelized pear salad with country ham, blue cheese, and creamy rosemary dressing

Roasted brussels sprouts with chow chow vinaigrette

Sausage-stuffed quail with sorghum barbecue sauce and fried apples

Maple and whiskey pudding with bacon crumble

This article was originally published in a past issue.

share

trending content

-

FINAL Vote for Your Favorite 2025 Southern Culinary Town

-

Get To Know Roanoke, Virginia

-

A Brief History of Shrimp and Grits

by Erin Byers Murray -

New Myrtle Beach Restaurants Making Waves

-

FINAL VOTING for Your Favorite Southern Culinary Town

More From Key Ingredient

-

Flour is a Southern Pantry Essential in This Nashville Kitchen

-

Sweet Talk: The Sensuous Power of Local Honey

-

Caramel Delights

-

Jason Stanhope’s Famous Celery Salad

-

Little Bursts of Summertime