Charleston is eating up Tina and David Schuttenberg’s brand of Sichuan at their kitschy hot spot Kwei Fei

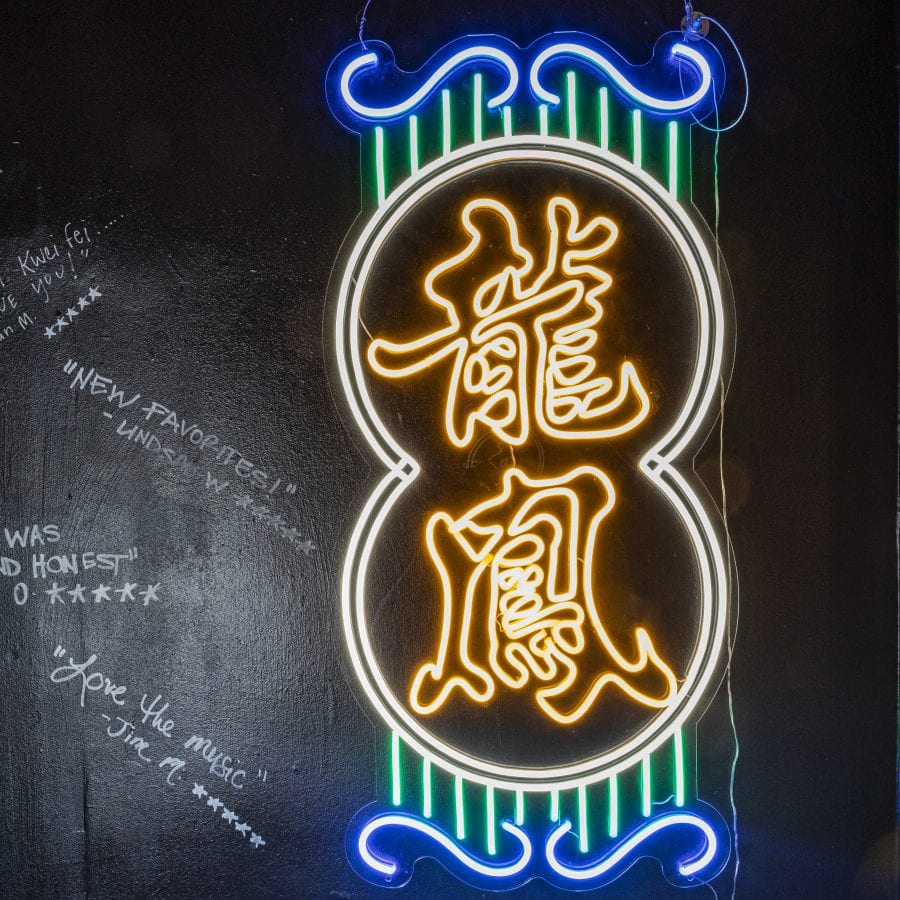

Lest the uninitiated think they’re walking into a subdued situation, Kwei Fei’s hand-painted sign says it all. Loud Hot Vibes underscores the restaurant’s name in taxicab yellow, offering fair warning that inside the music is bumping and the food, bold. “We’re not for everybody,” says chef David Schuttenberg, who opened the Sichuan spot that—despite his word of caution—is all the rage among Charleston, South Carolina’s restaurant-going public, with his wife, Tina Heath-Schuttenberg, late last year. “But it’s the vibe that we want: fun and communal and boisterous.”

While Charleston’s culinary star has been shining brightly for years, locals had long lamented the city’s dearth of Chinese restaurants. Sure, there are the Cantonese mom-and-pops that are tucked unassumingly into every other strip mall in America. But unlike other food cities of the Holy City’s caliber, regional Asian cuisines in particular had yet to find a foothold for a host of reasons. So to say that the community has embraced Schuttenberg’s brand of Sichuan is putting it mildly. Post and Courier restaurant critic Hanna Raskin hailed it as, “the great Chinese restaurant that Charleston has long awaited.”

Such props have been a long time in the making. After a decade working in IT for IBM, Schuttenberg left the corporate world for the New York campus of the French Culinary Institute. He landed his first cooking job at Tom Colicchio’s Craft, which he later spun into stints working with some of the city’s hottest chefs at the time, including six years with Zak Pelaccio of Fatty Crab fame.

The Schuttenbergs were at the height of their New York careers—he as the chef at Dickson’s Farmstand Meats and she as creative director of Dean & DeLuca—when they moved their family to Charleston with the hope of eventually opening their own place. The first two years were marked by false starts: The trio of restaurants Schuttenberg had opened with his friend Damon Wise closed within year and a subsequent gig as executive chef at the long-established Fish fizzled, leaving the couple to question whether or not they belonged.

But with the support and encouragement of friends in the local restaurant community, they forged ahead with a twice-weekly pop-up at the Daily, a market and cafe. “We said, ‘We’re going do this and it’s either going to work or we’ll leave,’” Schuttenberg says. The decision to focus on Sichuan was an easy one: “It’s my favorite style of Chinese food and there’s none down here.

So, I taught myself how to cook it.” With her background in marketing, Heath-Schuttenberg knew word would spread if they could lure people who worked in restaurants, so they stayed open until midnight to accommodate the F&B schedule.

Kwei Fei the pop-up was a hit, and a year later, the couple found a permanent space for it on suburban James Island. On a shoestring budget, they went casual kitsch on decor with vintage paintings, tropical plants, and pops of yellow paint. “As two white people, how are we going to open a Chinese restaurant and not pretend to be something we’re not?” Heath-Schuttenberg says. “I wanted it to feel like you’re having Tiki cocktails in the basement.” The quirkiness extends to the 1,090-song playlist compiled by Schuttenberg, a former rock band front man (the Phoenix New Times in 1996 dubbed him “Arizona’s bad boy of ska”). “I want music to be in the forefront of the experience. I want people to hear it and go ‘Oh my God, Sabbath during dinner, that’s weird.’ And then the next song might be Sinatra,” he says. “If you have that kind of jarring change in music, people notice. I want people to be aware that there are the same things happening in the food.”

Vibes aside, it’s the food that’s the standout at Kwei Fei. Schuttenberg weaves Lowcountry ingredients into Sichuan classics seamlessly, like a stir-fry of butter beans with chile paste, and noodles with Sea Island red peas. And while some dishes bring the heat, he leaves room for layers of nuance. “I love how Dave’s food slaps you in the face with flavor and spice,” says John Lewis, owner of Charleston’s Lewis Barbecue. “He’s not afraid to be bold in his cooking. Every time I try a new dish he’s created, I’m blown away by its complexity.”

On a recent trip to China—the couple’s first time there—they were inspired to learn they’re on the right track. “It would have been mortifying to eat this food in China and find that we’ve been screwing it up for two years,” Schuttenberg says, half- jokingly. But their experience was quite the opposite. Heath-Schuttenberg recalls digging into a bowl of liangfen (jelly noodles) in Chengdu when it struck her. “It was maybe the third stop of the day, and I was like, ‘Oh, David’s doing really good work.’”

Hui Guo Rou

Hui guo rou, or twice-cooked pork, is a Sichuan classic made by boiling and stir-frying pork belly with leeks and fermented black beans.

Sichuan Cucumbers

Sea Island Noodles

Laziji

Laziji is stir-fried chicken tossed in aromatics, scallions, and dried chiles. The finished dish gets another kick of heat from spicy chile crisp. Kwei Fei makes its own by pouring hot oil over a mixture of chile flakes, garlic, shallot, salt, and a touch of sugar. Schuttenberg says he uses it on everything. “We even put it on vanilla ice cream here at the restaurant.”

Butter Beans with Chile and Chives

YOUR SICHUAN STARTER KIT

Find these pantry essentials at Asian grocers or online

Black vinegar: With notes of caramel and malt, it has a depth that other rice vinegars lack.

Cornstarch: Mix with water to thicken sauces.

Doubanjiang: An essential building block of Sichuanese cuisine made by fermenting chiles and fava beans together in earthenware crocks for up to eighteen months. Look for Pixian Dan Dan brand.

Dried chiles: Schuttenberg uses dried Tianjin chiles, which are woodsy, earthy, and spicy, as well as thai chiles, when he wants to give a dish an extra kick.

Fermented black beans: Aka little flavor bombs that aren’t black beans at all, but yellow soybeans that have been steamed and fermented for months in a sealed container.

Garlic, ginger, and scallion: The holy trinity of aromatics not only in Sichuan cooking, but in Chinese cooking in general.

MSG: A naturally-occurring amino acid, monosodium glutamate has a bad rap but the FDA deems it perfectly safe. Schuttenberg uses it in his marinated cucumbers. “If you feel you are sensitive to it, feel free to omit, but I can tell you that most people who think they are, generally are only when it is overused.”

Pickled chile paste: Can be tricky to find. Sambal oelek is a worthy substitute.

Rice vinegar: Look for Marulan brand. Soy sauce: For recipes that call for soy sauce, Schuttenberg prefers a half and half blend of the light and dark varieties.

Sichuan peppercorns: The flowering part of the prickly ash bush, these citrusy, floral “peppercorns” are responsible for the numbing quality found in many Sichuan dishes. The Kwei Fei kitchen stocks the whole red and green ones and grinds them by hand.

Shaoxing wine: An aged, fermented rice wine used for marinating, as well as finishing stir-fries with a hint of brightness and acidity.

Sesame oil: Look for Kadoya brand.

Spicy chile crisp: Schuttenberg modeled Kwei Fei’s “angry lady” table sauce on Lao Gan Ma-brand chile crisp.

share

trending content

-

New Restaurants in Arkansas

-

Shrimp and Grits: A History

by Erin Byers Murray -

Tea Cakes, A Brief History

by TLP Editors -

Gullah Geechee Home Cooking

by Erin Byers Murray -

A Cajun Christmas Menu

by TLP Editors

More From At the Table

-

High Tea, Southern Style

-

10 Leftover Recipes To Clean Out Your Fridge

-

Country Captain Shrimp and Grits

-

10 Nonalcoholic Drinks for Dry January

-

Our Most Popular Recipes of 2023