The country’s oldest quail farm is infusing local farmlands with new life

Drive through much of South Carolina, venturing off the highways onto state roads with stop signs and small towns, and you’ll see miles of farm-land stretching in wide expanses to the horizon, row crops crowned by irrigation equipment, or small signs that announce farm-fresh eggs near a gravel road. It’s beautiful, peaceful, and seemingly idyllic—all of which is sometimes true.

But farming is a messy business. It’s almost inevitable to get dirt on the floor when you take off your boots. There’s often a pile of not-quite-working equipment awaiting repair behind a shed. And when you’re raising animals, there’s manure.

A lot of manure.

In South Carolina, as in many states, what happens to manure is regulated by the Department of Public Health (formerly DHEC). Most farmers spend thousands of dollars annually to dispose of it properly, and in an industry where margins are tight and the basic premise involves working with the unpredictable elements of weather and climate, that money adds up.

However, Brittney and Matt Miller, second-generation owners of Manchester Farms in Columbia the oldest quail producer in the United States—have found a fertile link with other local farmers by committing time and ingenuity, and building infrastructure to reimagine a waste product into an asset that can strengthen soil.

Manchester Farms processes close to 80,000 Pharaoh quail per week, and they have 300,000 laying quail that produce eggs as well. While the eggs are available in a variety of retail grocery stores as well as in the wholesale market, the quail meat primarily shows up on restaurant menus across the country, from Lowland in Charleston to The Antler’s Room at Hotel Gramshammer in Colorado.

All that quail adds up to close to 2,000 tons of manure produced in 2024 alone. In order to keep the laying condos clean and the farm operating as it should, the Millers invested in a conveyor belt system that catches the manure and moves it out of the barn a few times a week.

“You know, it’s kind of a dirty, messy job, but we’ve got it dialed in pretty well,” Matt Miller says. What initially started as a partnership in 2020 with a nearby sod company to make compost has grown into a “litter farm delivery” arm; a small fleet of trucks services a 50-mile radius of the quail farm. These days, there’s a waitlist of farmers who are lining up to purchase quail manure, anxious to be able to use a nearby source of natural fertilizer.

“I’m trying to back off my synthetic inputs and put some natural fertilizers back on the land,” says Brad Stowe of Belleville Farms in St. Matthews, where he grows Jimmy Red corn, Abruzzi rye, soybeans, cotton, and peanuts on 750 acres. Inputs are agricultural lingo for what farmers add to the soil (usually shorthand for nitrogen-heavy fertilizer) and, he says, “integrating cows and the quail litter is a good way” to make progress toward his regenerative farming goals.

Stowe doesn’t use quail manure on all of his farmland but focuses on the corn and rye fields. In 2025, his goal is to purchase 300 tons of quail manure from Manchester, spreading around two tons per acre, which will be his biggest purchase yet.

“I would say there is a 25 percent savings [over synthetic inputs], and that savings goes along with the added benefits I see,” he explains. “Whereas with a synthetic fertilizer, a lot of time you get a lot of vegetative growth, attracting deer; this quail litter is slowly releasing

nutrients, so you don’t get all of that.” And since Stowe only strip tills (which allows for minimal soil disturbance), most of the manure lies on the soil as top dressing, acting like a mulch to further stifle weed growth.

“I have found it to be profitable to put animal manure on the ground. As a farmer, I see ground that hasn’t had a history of that, and I don’t feel like the soil is as resilient as my home farm, where I use it,” Stowe says. “I honestly think it takes two to three years to build up and really start seeing that soil difference.”

That slow-release theory is supported by Zack Snipes, assistant program team leader of horticulture for the Clemson Cooperative Extension Service. “Not only does a natural input like poultry manure provide a steady release of nutrients that benefit the plants, but because of its natural chemical complexity, it adds to the health of the soil as well,” Snipes says. “Unlike synthetic fertilizers that are a flush of easily plant-

digested compounds, soil microbes have to break down the materials, and this contributes to the health of the soil, which benefits the farm long-term.”

Matt Lee, cookbook author and now farmer, too, of MC Lee Farm on Johns Island, grew 10 acres of Wrens Abruzzi rye last season and ordered 27 tons of quail manure from Manchester to spread on three different fields. “The difference in growth between fertilized and unfertilized pastures was dramatic,” he says. “The fields with the quail manure popped up with lush green winter peas by mid-March, the pea vines and tendrils so thick you could barely trudge through them, and the rye in those fields had an extra 10 inches of height to them by the end of the season.”

Quail manure is especially good for growing grains, he’s learned, because of that slow release of nitrogen. If it’s too fast of a flush, the grains will grow fast and skinny and fall over in the wind, he says. “A gentle nudge is what we’re looking for, and it’s nice knowing it’s an in-state, CertifiedSC source.”

Both Stowe and Lee are growing grains that will eventually be crafted into High Wire Distilling Company spirits, a company committed to centering their products on South Carolina grains that are grown using sustainable farming methods—which buttresses the state’s agricultural community. In fact, distillery owners Ann Marshall and Scott Blackwell continue the loop forward yet another step by “disposing” of their spent grain mash by working with livestock farmers who use it as a feed supplement.

Though modern in practice, this ancient farming technique stems from the idea that everything in nature has a use. It’s practical for strengthening soil as well as a farmer’s bottom line on both sides of the transaction. “For us to be able to provide an all-natural, organic fertilizer for $25 a ton is a huge benefit for the farmers,” Brittney Miller says. “And it’s a benefit for us to have it go somewhere that’s useful.”

keep reading

On the Road

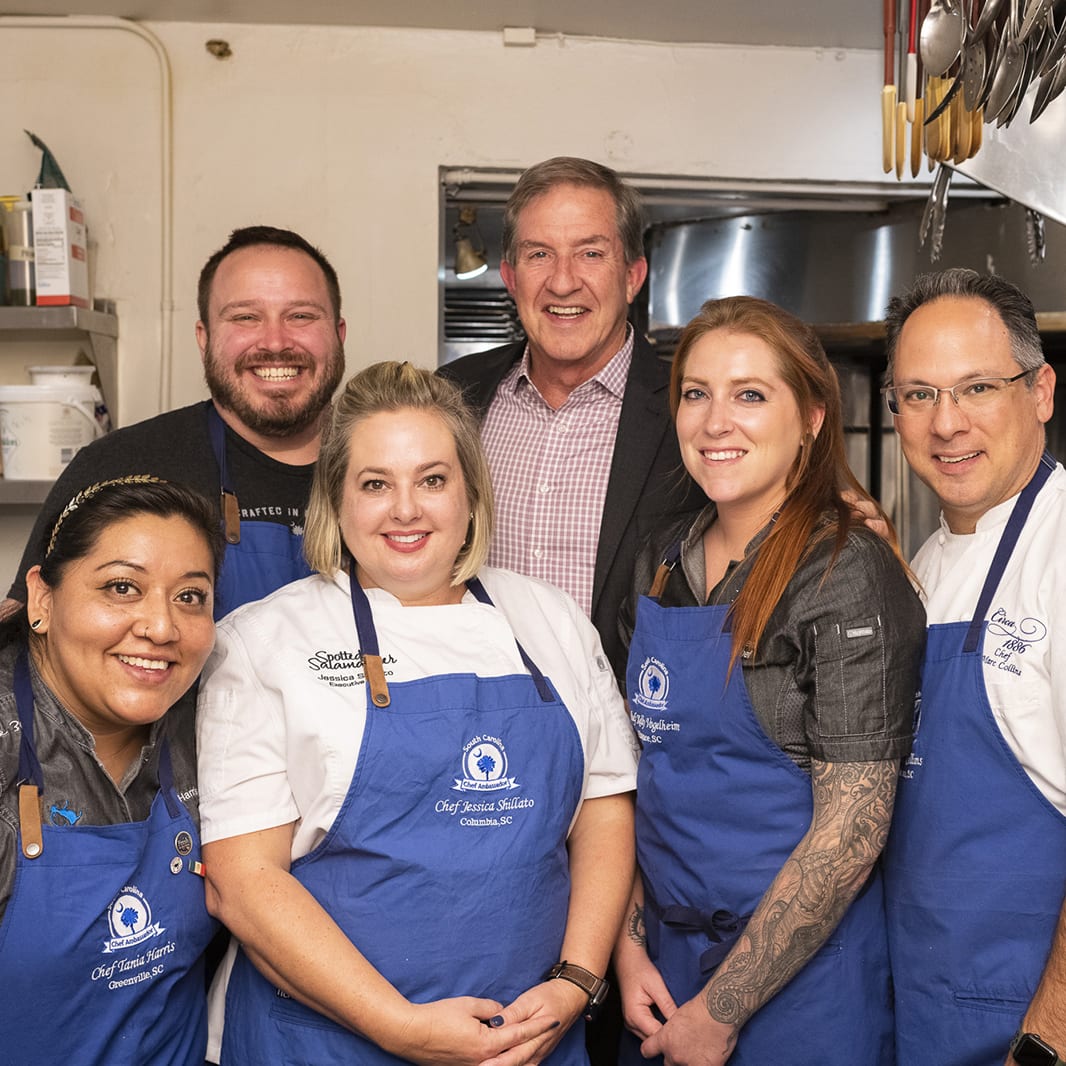

5 South Carolina Farm to Table Chefs

When planning your next trip to South Carolina, check out how these five chefs use Certified South Carolina ingredients straight from area farmers: Marc Collins, executive chef at Circa 1886 in Charleston, takes a deep dive into South Carolina’s history and the African, […]

In the Field

The Quail Whisperers

A family-run South Carolina operation is putting the birds on some of the world’s top tables South Carolina is quail country. Their numbers in the wild are not what they used to be, but they remain—hidden in the hedgerows […]

In the Field

10 Southern Innovators Changing the Game

These 10 innovators are taking action to tackle big food-focused issues around the Southeast and working hard to change the game.

share

trending content

-

FINAL Vote for Your Favorite 2025 Southern Culinary Town

-

Get To Know Roanoke, Virginia

-

Shrimp and Grits: A History

by Erin Byers Murray -

New Myrtle Beach Restaurants Making Waves

-

FINAL VOTING for Your Favorite Southern Culinary Town

More From In the Field

-

A Cajun Christmas Menu

-

Nina Compton’s Caribbean-Inspired Christmas Feast

-

Celebrate Moments with Biltmore